Is Britain a high or low tax country? Yes.

Tax is up, but many are paying less (and then there's France)

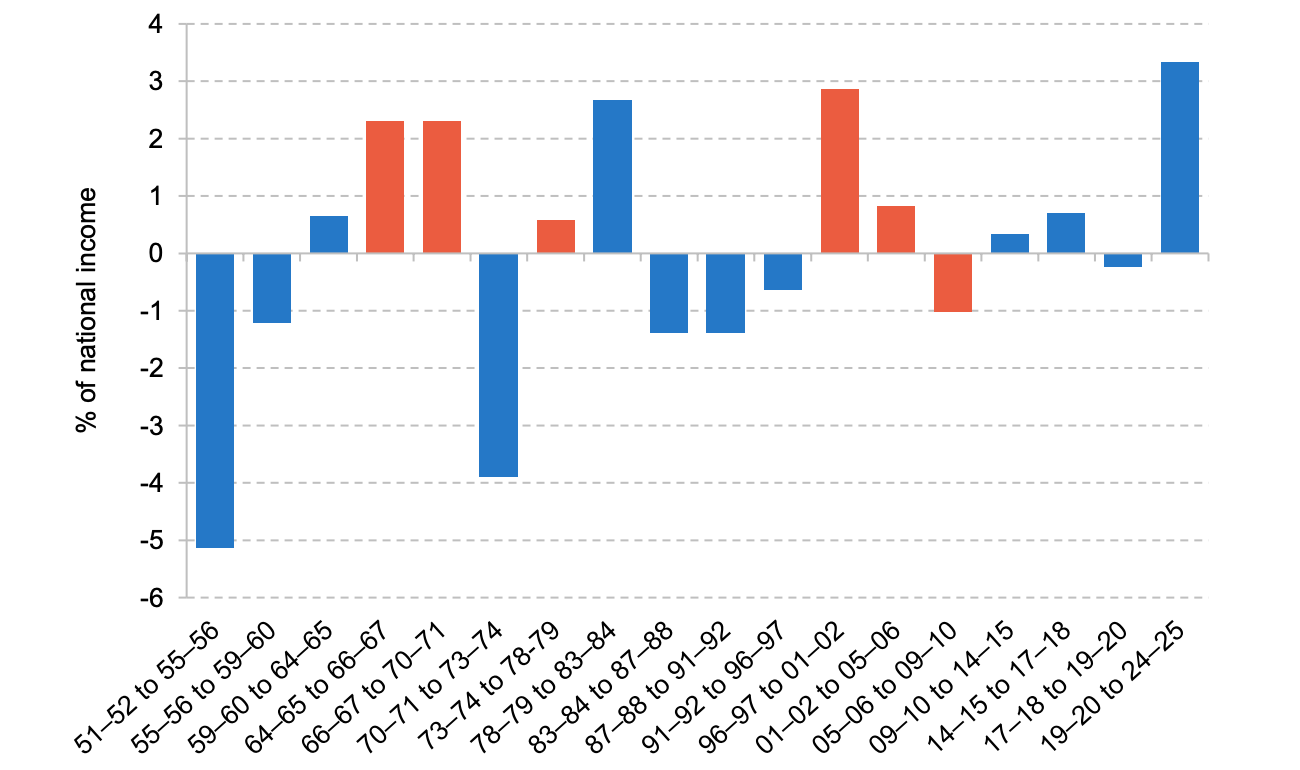

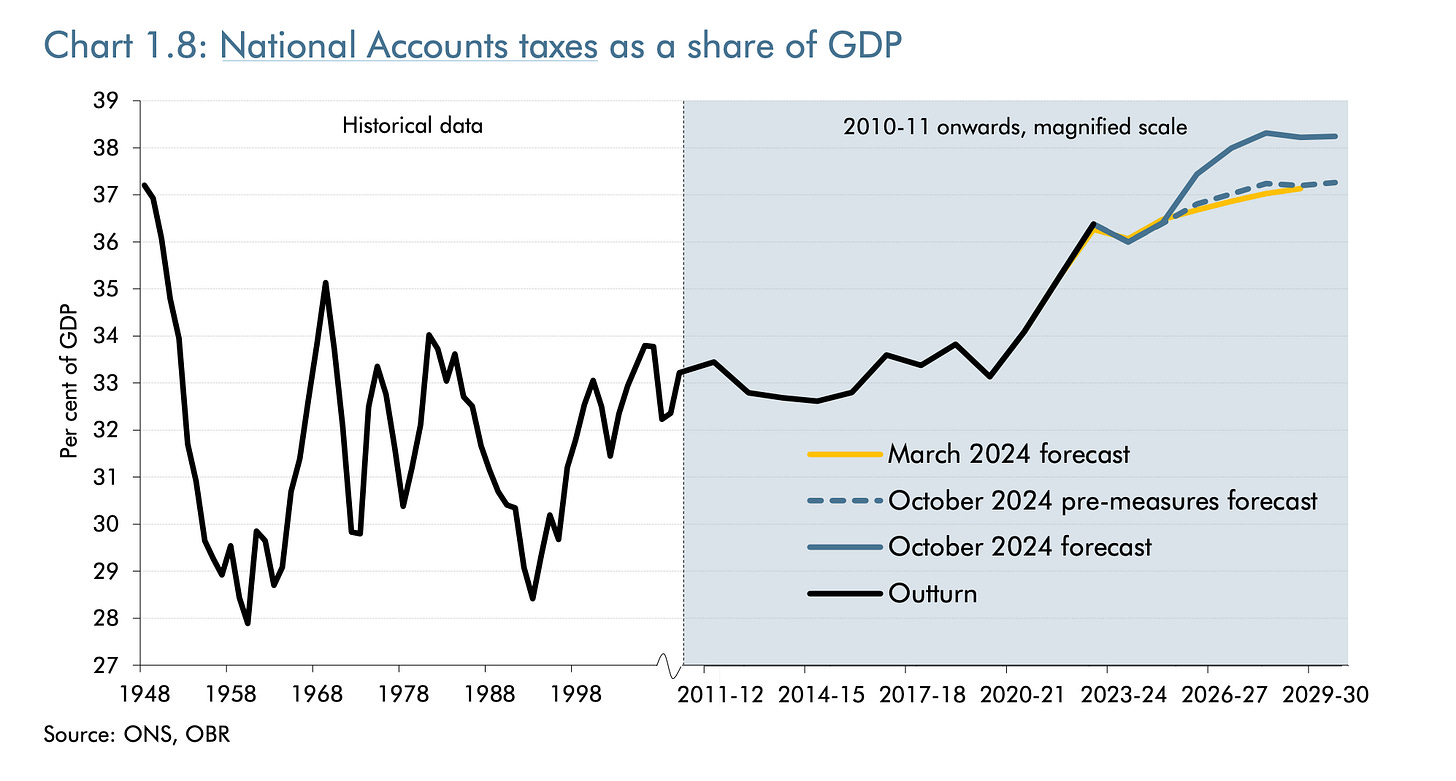

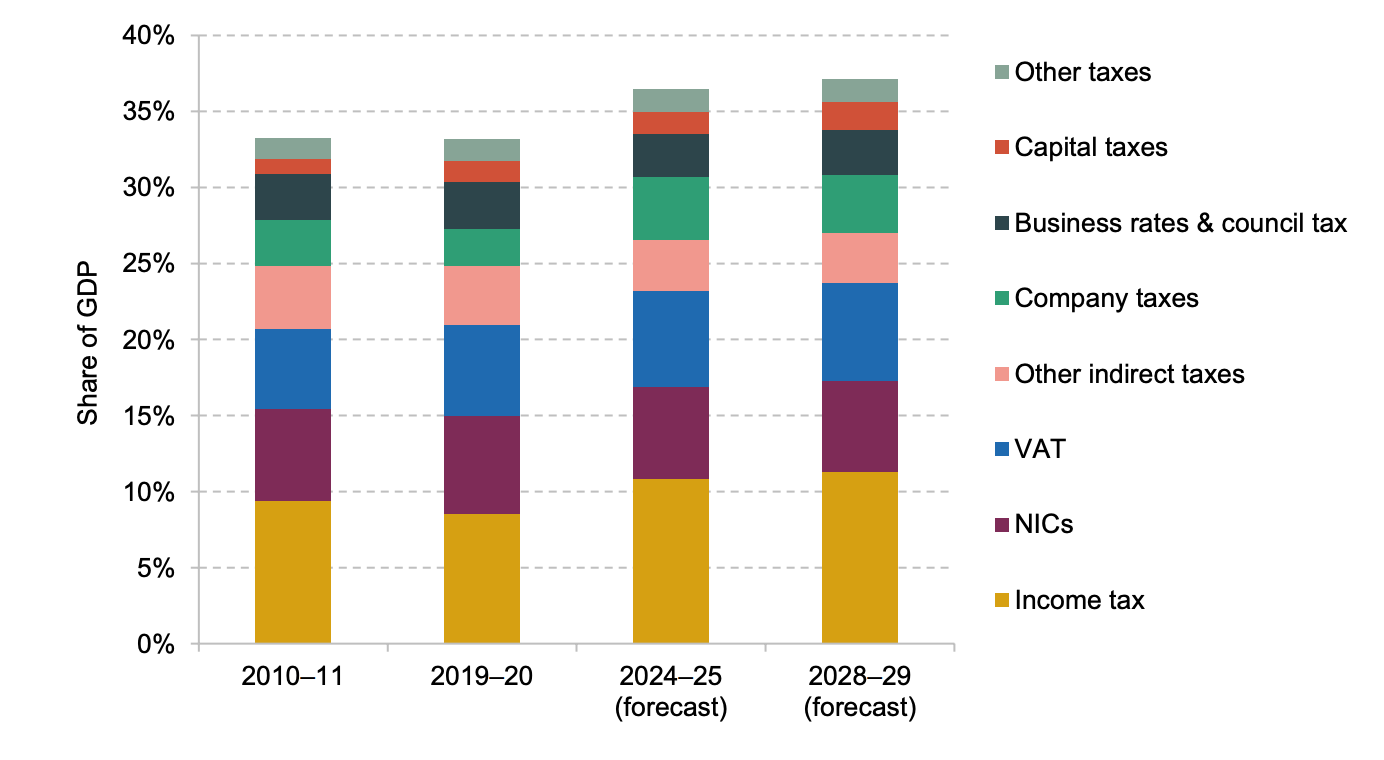

Taxes have been going up. Tax revenue as a share of GDP hovered around 33% from 2010 to 2019 but has jumped sharply since the pandemic. Indeed, the last parliament saw the largest rise in the tax take of any parliament in recent modern history, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS).

Then, the October 2024 Budget happened. As a result, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts that tax as a share of GDP will rise from 36.4% to 38.2% in 2029-30, driven largely by personal taxes, most famously the increase to employer national insurance contributions (NICs).

Given the continued poor performance of the UK economy, the dire state of public services and the need to spend more money on defence, it appears safe to assume that taxes will continue on their upward trajectory. Still, that is not necessarily conclusive evidence to say the UK is a high tax country.

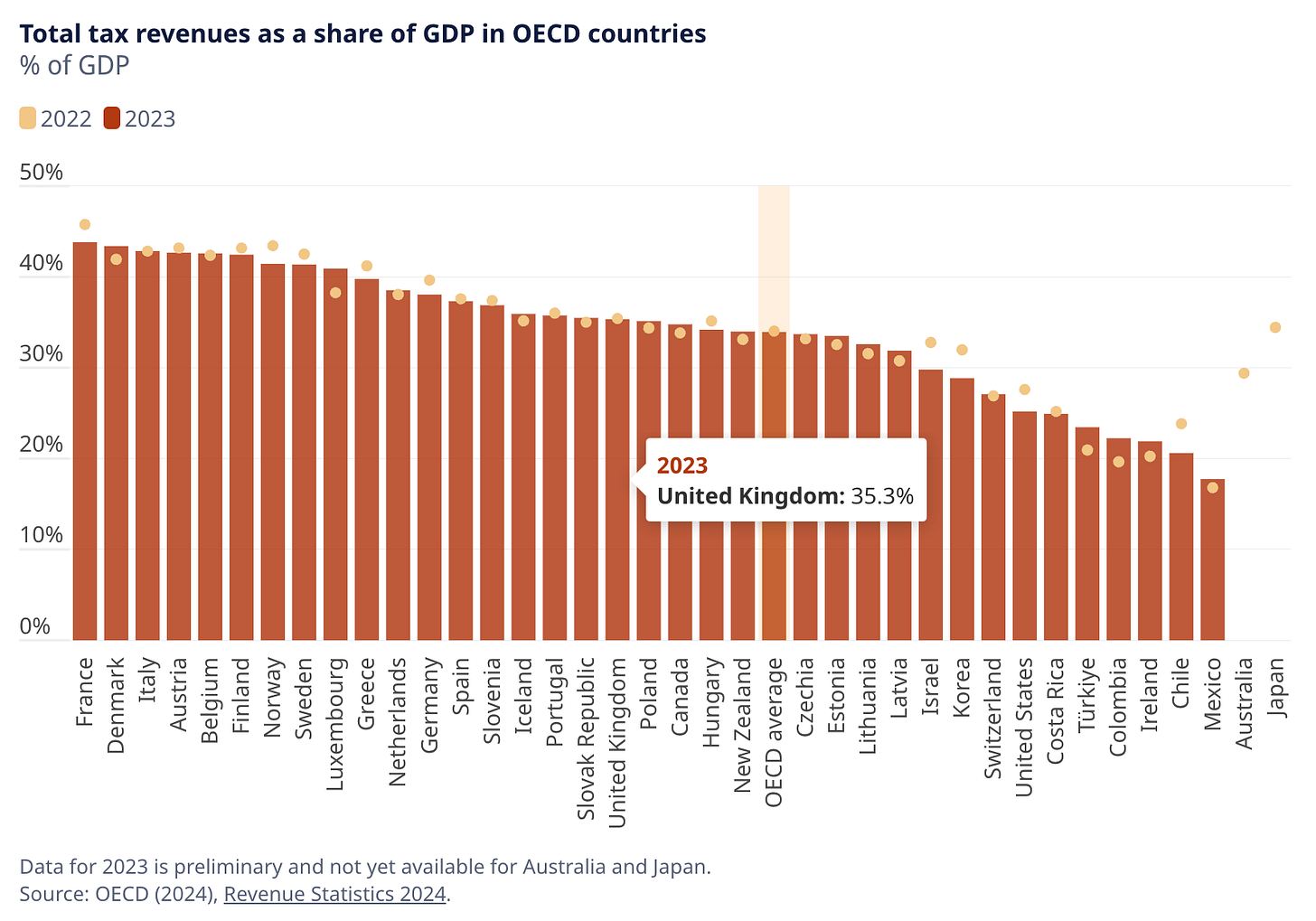

When it comes to tax revenues as a share of GDP, Britain has long been fairly middle of the road. The graphic below from the OECD, a club of mostly rich countries1, is from 2023, so the UK is certainly rising in the charts, but it is clearly no outlier when it comes to our fellow European economies.

While we’re here, I’ll note that the composition of the tax take has changed in recent years. Though nearly two-thirds of revenue continues to come from the ‘big three’, income tax, VAT and NICs, the proportion from the first two has risen, while the latter has fallen. Meanwhile, revenue from excise duties has dropped due to repeated real terms cuts to fuel duty2 and the continued decline in smoking.

Of course, there are all manner of distributional nuggets. One striking change since 2010 has been the impact of increases to the personal allowance. This has taken many low earners out of income tax entirely (while also handing a tax cut to the better-off). At the same time, not-so-stealthy freezes to income tax thresholds have resulted in substantial tax rises for higher income individuals.

The result? Simply put, the better-off are paying more income tax. As the IFS notes, the share of income tax paid by the top 10% of income tax payers rose from 53.5% in 2010-11 to 60.3% in 2023-24. Meanwhile, the top 1% of UK adults, that is people with incomes of roughly £160,000, paid around one-third of all income tax, up from a quarter two decades earlier.

This leads to something of a curiosity. Taxes are at their highest level since the 1940s, but income tax and NICs have been reduced since 2010 for most people. Indeed, at the point of the last election, the effective personal tax rate for the median earner with no children fell to the lowest point since 1975.

The gravest threat to our prosperity as a nation is not the headline figure for tax as a proportion of GDP, but kind of everything else. Ask yourself, how well are those public services performing for the level of taxation? What is happening to living standards and disposable income? What are we doing to boost the UK’s persistently anaemic productivity growth? In what direction are other indicators, such as child poverty, heading?

You may think that the tax system penalises employment, that council tax is based on ludicrously outdated valuations and that VAT exemptions generate distortions and compliance burdens3. You may well be right. But is Britain a high or low tax country? Yes.

Only took seven editions of Lines To Take to squeeze this in